There has long been a belief that the purest, highest, or most universal form of artmaking is revealed through the elimination of the essential; thus, “essentialism” has reigned as a discursive premise for artists' efforts to capture the essence of life: the perennial condition of human beings and reason for existence, raison d'être. Inspired by numerous philosophical terms, including Plato's idea of fundamental or universal entities, artists of the last hundred years (or more) have dedicated themselves to capturing abstract form in art as a possibility of penetrating the veil of material existence in order to reveal a spiritual reality, often inspired by the patterns and artifacts emerging from the most ancient societies. This reality can also be discovered in philosophical and aesthetic thought based on ancient historical (written) doctrines or on contemporary theories that refute the assumption that the artist is granted a kind of prophetic interpretation. The artist/philosopher's most recent dialogues examine the role that process and materials play in creating a new and personal form of production that reveals both the present and the past. It is within this category of essentialism that Fernando Varela's work can be placed.

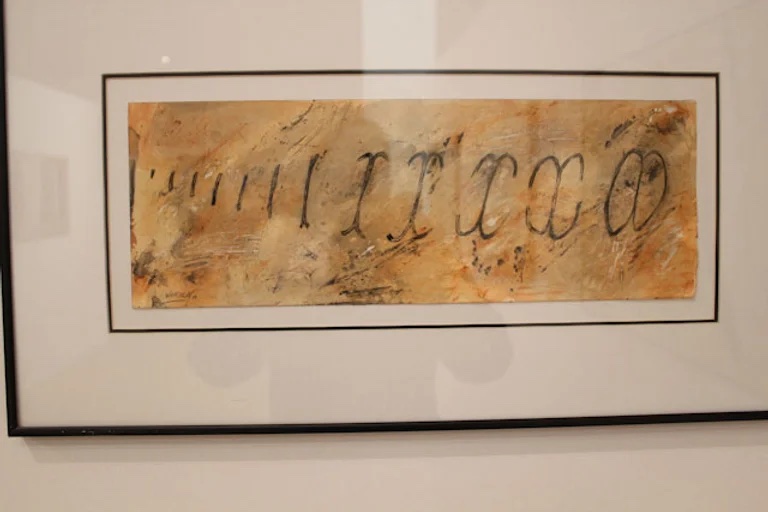

An encounter with the sweeping brushstrokes of pigment that interrupt the richly textured surfaces of Varela's work occurs, penetrating a portal to a spiritual world evocative of caves, or a rediscovery of art in its earliest origins. His constant engagement with sensual materials and his freedom to manipulate the most essential images on canvas allow the viewer to visualize an abstract idea as an associative psychological exercise through the crude application of paint that is as primitive as it is modern. Forged from dense and sometimes nervously repetitive artistic brushstrokes interrupted by patterns that frequently reference ancient texts, Varela's canvases and works on paper repeatedly utilize quasi-geometric elements, figures that transform into organic notations.

These figures become heroic figures steeped in legend, yet intimately linked to the history of humanity, beginning with cave drawings. It is in caves that the first human evidence unequivocally begins with the activity of men and women in art (these we can today call artists). For these ancient people, their work, which descends from the Paleolithic or Stone Age, was something necessary that provides the strongest perennial thread for the continuity of a universal language of signs and symbols. These marks of antiquity represent the essence of imaginary images, without the aid of written words, using only a formal language of line and color, and yet these prehistoric painters seem to still communicate with us. It has long been argued that the paintings and drawings in the caves of prehistoric Europe, Africa, and Asia were purely ritual activities—a process more meaningful than its results. It can also be noted that, beginning with the Action Painting of the 1940s, art returned to this aspect of the process with the inclusion of abstract signs and symbols that once again defy interpretation. Paleolithic painting is the same curious mix of the immediate and the ambiguous that appears in Varela's work, also difficult to penetrate its meaning due to its complex intellectual basis rooted in generations of signs. Nevertheless, the viewer is always aware that his works represent more than a decorative application of elemental designs on canvases that range from rich inlays to soft elegance. There is always a seriousness of purpose and commitment to expression that informs all the work, whether oil on canvas or mixed media on paper.

Varela's process represents an extension to the mastery of symbols, simplified as calligraphic brushstrokes that float over complex textures traced with references that act as palimpsests, constantly laminating, erasing, and reworking his canvases to reveal something new emerging from the depths. Drawings like caverns that transform innate knowledge and memories into two-dimensional still images, without considering a continuous narrative or perspective, Varela's process depends on multiple levels of intuitive marks, and what is ultimately revealed is a visual language read beneath the most recent tracing. Words, letters, and engravings, traced in a variety of resources, from the most direct, the alphabet, to the most complete, sacred texts from the Holy Book, reappear for many years and reveal his fascination with information systems, from the simplest to the most erudite.

Always seeking to understand how human beings share knowledge and express emotions, Valera explores signs, letters, and words and all their ramifications and implications throughout time. It is through some form of language system that civilizations have emerged from the darkness of the past, not only to connect with one another but also to communicate with the unknown. The artist works as a kind of priest, empowered to communicate with the spirit world; becoming a guide of the soul, assisting the viewer through the multiple layers of meaning present in his works. He also uses imagery to convey spiritual visions that tend toward the abstract and are based on combinations of natural and geometric forms, with organic and inorganic references.

Varela's profound fascination with basic forms and their way of interacting in time and space remains fundamentally present in all his works throughout the years. These images, despite their elemental simplicity, are always filled with meaning, from the spiritual to the secular—from universal to formal. As an artist, Varela may be inspired by a gravitation associated with his interest in the perennial condition of the human being, but he is also interested in the aesthetic arrangements of his forms within compositions that must achieve artistic success. The intellectual concept is associated with formal artistic meaning. His entire visual language is driven by a ritualistic will and a metaphysical knowledge that transcends time. The perennial condition of the human being is a drama that led him to analyze the essentials of visual language. Ovals, circles, and ellipticals become primary forms that highlight the great theme of creation, the essence of things. His handling of paint—a combination of hard edges and free, painterly areas—records duality in inspiration and intellection; in harmonious accord, male and female; in black and white, good and evil, and positive and negative. Large figures, or pure abstraction, eschew the image, becoming the most dramatic way to effect simple expressions of complex concepts and processes. The symbolism of an egg, the basis of creation, the ovum allows the artist to experiment technically without ever losing sight of its meaning. It would not be surprising if Varela called these images “primary forms.” Over many years, he developed an arrangement format dominated by large, repeated figures tailored to the ideas he wished to explore.

Marked by the dualism of oval and angular forms combined in a number of series, Varela's work on canvas or paper continually explores formal relationships as bases of intellectual thought.

In other works, Varela continues to combine simplified forms, or fields of color, with complex marks that entice the viewer into the depths of his planes. The addition of optical tends from side-by-side placements, from broad areas almost close-up but with valuable tonal contrasts. The layers of pigment tend to produce a strange complexity to the flatness of the forms, extending the artist's unique language through time. No matter how minimal the dominant forms, the image always remains resonant, simulating the vision of elemental totemic artifacts, phalluses, testicles, wombs, megaliths, and other figures. His visual language is as basic as the rhythms of primitive tribes and as elegant as the calligraphic style that has so long captured the imagination of the Western world. Now replaced by broad, sweeping gestures that glide across the canvas to leave generous paths of shimmering ink or paint over the rich surface, Varela's calligraphic marks add resonance to the poetic, lyrical mood of his works.

The combination of expansive brushwork, bold forms, and dense areas reveal a sense of archaism and mystery that is fundamental to the artist's intention to reveal a spiritual content in each work and his pursuit of a shamanic communication process through painting and drawing. Varela's keen sense of line, basic to all of his work, sets the stage for other connections that are always the means to reveal the essence of his objects. Drawing creates the marks that become messages. Painting operates through signs that are not so abstract as to be indecipherable. We may not know the exact meaning of the oval, or the peculiar split mark that also appears in his work, but we know they are symbols of something, and not mere decoration. We can derive a personal meaning for each, from the obvious references to the origin of creation in the ovoid/egg shape, to the concepts of duality, represented by his other, most familiar sign, a shape notation a-b. The signs Varela creates allow his paintings to go beyond what mere words or texts can achieve in approaching the mysteries of life and in considering the perennial condition of the human being. His works can invoke things through signs that connect to everything that was and still is in the present. Painting is the most immediate and direct method of communication for expressing his inner voices, and in the search for meaning in life, it is the reason for being, the raison d'Ñtre.